Life and death on the seven seas – Captain Gabriel Ahlfort

Svenska – English

From beyond the seas – A history of the Alfort family.

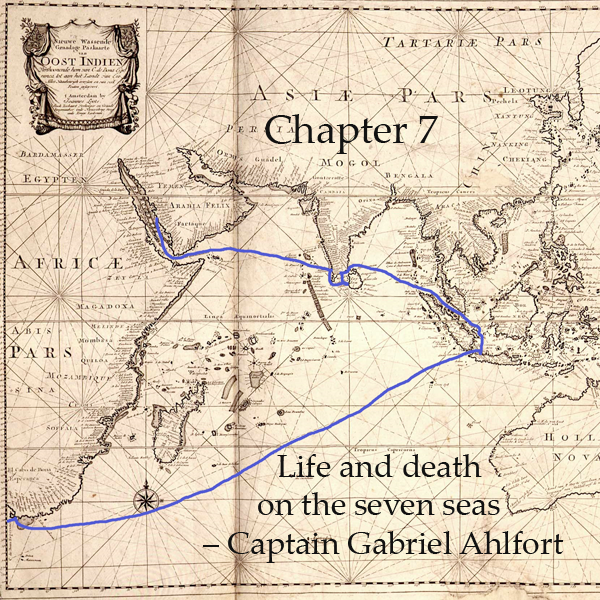

Chapter 7

Life and death on the seven seas – Captain Gabriel Ahlfort

© Esben Alfort 2014-2023

Captain Gabriel Ahlfort travelled to Indonesia, India and Mecca, and he knew the shores of Europe better than his home county. He saw some incredible things and had real stories to tell when he returned a wiser and stronger man.

Erik and Maria Sophia’s eldest son Gabriel Ahlfort had an eventful youth peppered with several perilous travels to such far-flung destinations as South Africa, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka and Mecca. He was so unusually well-travelled, in fact, that at his death in 1780 his obituary suggested that he had been to almost every place in the known world worthy of mention.

Captain lieutenant Gabriel Ahlfort, deceased on 10th January in his 77th year at his estate Liljeholmen in Torpa parish in Östergötland after having during his 30 years of service at the Royal Admiralty travelled to most places in Europe, Asia and Africa, and finally, like a true benevolent patriot, made his remembrance to posterity very well-deserved through commendable cultivation and stone breaking [at his estate].

Inrikes Tidningar 21 Feb 1780, translated from Swedish

The obituary appeared in the newspaper Inrikes Tidningar in the Swedish capital, where he seems to have been a known character, at least in the sense of being someone worthy of being mentioned in the papers. Eight years before, his agricultural skills had been praised in the same paper, as mentioned in chapter 5.

Like his father before him, Gabriel had wanted to become a captain in the navy, and like him he had volunteered for a job at the main naval base in Karlskrona in spring 1721, having reached his seventeenth year. On 1st April he was accepted and conscripted in Admiral Carl Hindrich von Löwen’s company.

Though Gabriel never actually experienced war at sea, the navy as a career choice was in general very far from being peaceful and danger-free. Sweden’s status as a European superpower was in its last phase of collapse, with the Russians ravaging the northern coasts of Sweden continually and well on their way to conquering Finland as well as Livonia and Ingria. In principle, a peace treaty was under way, but in fact open war was raging, and on 25th May a major battle took place near Sundsvall in northern Sweden in which a small Swedish troop was attacked by a Russian army more than ten times its size. It was to be the last battle in the long war which ended in severe territorial losses never to be regained.

On this background, the letter arriving for Gabriel on the last day of May ordering him to travel to Karlskrona, though eagerly awaited, must have caused mixed feelings. There was nothing more honourable for a young man to do than to join the navy or the army, but everyone knew that he might not be coming back again. He would be very lucky not to be killed in an enemy attack or die from one of the fatal illnesses to which many seamen succumbed sooner or later, and of which Gabriel would also have his fair share.

A mere week after the arrival of the letter he bade his parents farewell, and another week’s travelling over land saw him in Karlskrona, where he was formally conscripted on the following day, 15th June 1721. His first assignment was to study the basics of seamanship with the experienced commander Erland Hederstierna on the ship of the line Enigheten, which he boarded two weeks later.

With her 94 or 96 guns (sources differ on this point), this ship was built by the famous Charles Sheldon in 1696. It had participated in the expedition to Denmark in 1700 in which Gabriel’s father Erik had also served as a lieutenant, as well as the famous battle of Køge Bugt 1710 and at Rügen 1715. Gabriel must have felt that he was continuing his father’s good work. At the battle of Rügen, the captain had fallen, but Hederstierna (or Scherna as he was then called) had taken over the command and had done it so well that nobody realised what had happened. He was later ennobled for his deeds and given the name Hederstierna, ’Honour Star’.

Gabriel also did quite well as a seaman and rose through the ranks as a högbåtsman (’high boat man’, 4/5 1726), arklimästare (master of artillery, 1737), and at the same time or very soon after also konstapelsmat (vice constable, 30/6 1737), moving on to konstapel (constable, 14/7 1740), löjtnant (lieutenant, 13/1 1742), and finally kaptenlöjtnant (captain lieutenant) before his retirement in 1751. Although he apparently never rose quite to the rank of captain as such, he was always addressed as Captain Gabriel Ahlfort in his later life when he had settled at the family estate Liljeholmen again, so it is possible that he received the title on leaving service. His father would have been proud, if the old man had lived to see his first promotion.

We can reconstruct Gabriel’s experiences abroad in exceptional detail due to a unique diary, excerpts of which were published in the fifth volume of the historical series Från Sommabygd till Vätterstrand in 1955. The diary has been handed down through the generations in the branch of the family that has kept the tradition of working in the navy and is now in the possession of the admiral Peter Nordbeck, seven generations down from Gabriel. The style of the so-called diary is very dry and concise, except when his feelings run away with him on the subject of his beloved, and occasionally his dear parents, whom he probably learned to miss on his long voyages to far-flung coasts.

Initially, I wondered at this unemotional style, because some of the stories are quite gruesome and upsetting, but then I realised that he seems to have written it at a later date, based on old notes in his logbook, and suddenly it all made sense. The title on the cover is Amsterdam d. 29 ochtober Anno 1733, so he definitely cannot have written anything in it before that date. He must have started it on his way back from Amsterdam, when he was heading home to get married. Perhaps he wanted to record his experiences for the benefit of his fiancée?

Whatever the reason, we are very fortunate to have this diary so we can enjoy the fantastic story of his voyages across the seven seas. Its contents are further corroborated by an independent source, Gabriel’s so-called merit list in which he gives the official version of his career at the occasion of his retirement.

Madagascar’s pirates – Gabriel very nearly makes history

Gabriel only got a month to learn seamanship aboard Enigheten before being commanded on a dangerous mission, which was meant to go as far as Madagascar!

A band of pirates – mainly English criminals – had founded a free colony based on Île Sainte-Marie, an island off the east coast of Madagascar known today under its Malagasy name of Nosy Boraha. Great swathes of the Madagascan coast seem to have been dominated by local pirate chieftains and ‘kings’ who made a living from pillaging merchant vessels passing by en route between Europe and Asia. This had been going on since the 1680s and was a serious problem, especially for the East India Company. Consequently, the pirates were heavily persecuted and started to fear for their safety.

They were therefore on the lookout for a protective European superpower who would pardon and defend them, and at that time Sweden was an obvious choice, though Britain, France and Denmark were also contemplated. They wanted, in fact, to give up their buccaneering lifestyle and settle as lawful merchants again, within the borders of a sovereign nation. They had, after all, only wanted to make a living just like everybody else.

Their emissaries first met with the Swedish king Karl XII in 1713 in the Ottoman Empire, an ally of Sweden, offering him money and vessels if they would be allowed to settle on Swedish soil without fear of persecution. They would furthermore turn Île Sainte-Marie into a Swedish colony, leaving a sufficient number of pirates on the spot to secure the foundations of the new colony, where they would conduct legal trade on the Orient under the Swedish flag.

In 1718, the Swedish king accepted this proposal, though declining the cash. It was after all looted money, and although Sweden was in bad need of cash due to her overambitious wars he may well have feared the political consequences of accepting it. He invited one of the pirates’ chieftains, Captain Caspar Morgan, to Sweden, where he formally instituted him as the future Swedish viceroy of Madagascar.

What this colony would have meant for the future of Madagascar and Sweden we can only speculate, because the king was famously killed later that year before any of it could be realised. Back in Gabriel’s home area, people in the neighbouring parish of Asby had wondered at the eerie chiming of the church bell on candlemass eve that year, as there were supposedly no one to pull the string. According to a note in the church register, this was an omen of death, and it boded ill for the king.

On candlemass eve 1718 it happened that the small bell here at Asby chimed by itself some 3 times during the day 9, 12 and 2 pm – 4 or 5 chimings each time, this old paritioners said were supposed to mean an important and prominent gentleman’s death in Sweden whereupon indeed followed that our most gracious king Karl XII was shot to death at Fredrikshall in Norway 30th November the same year 1718.

Translated from Swedish

Karl XII was shot in battle, but supposedly not by the enemy. An expedition bound for Madagascar was then already on its way and had got as far as Spain when news of the king’s demise reached them and forced them to return to Sweden.

Now, a couple of years later, there were plans to reopen the contacts with Madagascar and attempt to carry out the deal. After long top-secret discussions, the two frigates Jarramas and Fortuna were chosen for the task, a third vessel being added later. The expedition was commanded by Captain Ulrich Ulrich, and included Gabriel Ahlfort on its payroll aboard the Jarramas, which was named after the Ottomans’ nickname for the belligerent Swedish king, Yilderim Yaramaz ’the naughty thunderbolt’.

In spite of their precautions, the Russian Tsar Peter the Great got news of the arrangement and attempted to forestall them. He sent two frigates on the secret mission, but fate would have it that they were so damaged by storms in the Baltic Straits that they were forced to return. The Russian mission was never reopened after this failed attempt.

Sweden’s brief fling with the Madagascar-based pirates is one of the strangest forgotten nooks of Swedish history, or perhaps one should say history as it might have been. So little is known about it, in fact, that Gabriel’s diary may be considered an important historical document.

Like its Russian counterpart, the Swedish expedition was destined to end in complete and humiliating failure, in this case due to bad leadership. They only ever reached Cádiz in Spain, a town which Gabriel would revisit several times in his career. On the way there, they survived dangerous storms and perilous sandbanks, and even an attack by Turkish pirates, but it would all be in vain.

The Jarramas left Karlskrona for Madagascar on 6th August, barely two months after Gabriel’s first arrival in the navy port. The plan was to go via Gothenburg to Île de Baste by Morlaix in northern Brittany, where they would meet up with the newly appointed viceroy Captain Morgan and his fleet. Unfortunately, some equipment for the Swedish ships was delayed, so Jarramas had to depart alone.

They sailed via Gothenburg across the North Sea and down the English Channel, where they were impeded by strong southeasterly winds and hit a dangerous Flemish reef near Calais. They only just avoided breaking the ship. This is one of the perilous experiences which Gabriel merely notes down in his diary as if they were nothing out of the ordinary. He cannot possibly have been so hardened at this stage; we must attribute it to the diary having been written many years later.

In the meantime, Captain Morgan had left his nephew, Captain Galloway, in charge of his fleet while he remained behind in Morlaix, where he waited for the Swedish frigates to arrive. However, for reasons unknown, but possibly related to the stormy weather which had almost cost him his ship, Captain Ulrich on October 1st decided to sail past Morlaix and continue directly to Cádiz against his orders, and without sending word to Captain Morgan. Perhaps he thought that as the other Swedish ships had been left behind, Morgan might just as well wait for them.

Leaving Brittany behind, they sailed out onto the Atlantic and immediately met danger in various guises. Barely two days later, they lost their mainmast to the raging seas, and on the very same day they were attacked by ”Turkish” pirates who, however, decided that they had bitten off more than they could chew.

3rd [October] our mainmast went overboard, the same day two Turkish vessels came up to the side of our ship and would board, but when they sensed that were carrying 11 guns and a large crew they took flight.

Translated from Swedish

The ”Turkish” pirates were in actual fact probably ”Barbary” pirates from Algeria. They had a long tradition of collaborating with protestant British pirates against catholic ships. It is possible that they really left the Jarramas in peace on realizing that the crew was protestant and not catholic, and that their British partners would therefore not be happy if they found out.

It seems ironic that the Jarramas ought really to have had its own Madagascan pirates on board from Morlaix, if only Captain Ulrich had obeyed his orders, but at least they arrived safely in the Andalusian port of Cádiz on 10th October.

What made the expedition fail was neither storms nor pirates. The real blow came when it suddenly transpired that the money had run out, so the expedition could not continue, and anyway it had clearly become too late in the year for going around the Cape of Good Hope. Captain Ulrich could only think of one solution – they must return to Sweden. The expedition was thus a complete failure, and one can imagine that the crew would have been quite disappointed. Perhaps that is why Gabriel doesn’t mention the return journey with a single word.

It took them more than six months to get back. On 23rd June they arrived in the familiar port of Karlskrona. There was no welcoming committee; people were appalled at Captain Ulrich’s having spent all the money without achieving anything. He was tried by a military tribunal, and another expedition was ordered to take place with a different captain. Gabriel would not be participating in this strange project again, and indeed Sweden would never acquire the colony of Île Sainte-Marie.

The secretly betrothed

In 1723 Gabriel was promoted to artillery expert (arklimästare) and departed for Swedish Pomerania on the cargo ship Anklam (named for a place in Swedish Pomerania) with orders to fetch oak timber for the construction of new ships in Karlskrona. His destination is likely to have been Stralsund.

The Pomeranian town had recently been returned to Sweden after the brief occupation mentioned in chapter 5 in connection with the soldier Per Hurtig, and in January the following year Gabriel went there once more, this time with Swedish troops from Småland.

After this trip, he was allowed to visit his parents at Liljeholmen for three months from 23rd February to 30th May. This seems to have been an uneventful visit; at least he does not tell us what happened during those months. Instead he goes on to tell the story of his career as it continued after his holidays.

He was first ordered aboard the cargo ship Wolna bound for Riga in Livonia. Riga was an important export port for mast timber and hemp, which was exactly what they were after. The next summer saw him leaving for Riga once more, this time on the royal warship Solen.

Even these seemingly peaceful voyages across the Baltic Sea could be perilous. At three occasions on the passage between Sweden and Livonia strong winds forced them to land in the protective natural harbour at Slite on northern Gotland. They would then stay at anchor for about 10 days before being able to continue.

After another visit to Stralsund to collect oak timber, he was once more permitted to visit his family at home. He returned to Liljeholmen on 27th October 1725. By then, his sister Maria Catharina’s affair with Jonas Andersson had been discovered, but the first trial had yet to take place.

Gabriel stayed for another six months, and this time something interesting certainly did happen: A strong love was awakened in his young breast as he met his very young cousin Anna Brita Wetterström. Perhaps he was inspired by his sister’s bold insistence on having her way in love, because in total secret from everyone he actually went and proposed to her – in spite of the fact that she was only 10 at the time – in the hope of being able to marry her the day she turned 18!

27th [October 1725] I arrived home. And during my visit I proposed to Anna Brita Wetterström and we got engaged, however in secret, she 10 years and I 22 old.

Translated from Swedish

They would not be able to tell the world of their engagement for the next eight years; he had a lot of journeying to far-flung places to do, and she was much too young to go around accepting husbands. It is perhaps no coincidence, however, that two years previously his then barely 14 years old cousin Maria Christina Svanhals had married a local nobleman. This news would have told Gabriel that he had to secure her hand very early on lest someone else come along and snatch her away before he could make himself a name in the world.

Of course keeping his mouth shut would hardly be a problem for him when he was away on foreign seas. He would never waver in his devotion, however, as is clear from his longing notes about her further on in the diary when he had been away for a very long time.

He needed a promotion in order to be able to marry her, partly because it would take a much larger income to provide for them both and also have spare money for the upkeep of the family estate, but also because Anna Brita was of noble birth, being the daughter of Gabriel Gyllenståhl’s daughter Hedevig Gyllenståhl and his secretary Anders Wetterström, and she would hardly be allowed to marry him unless he distinguished himself somehow. So far, he was only a master of artillery who had participated in a famously unsuccessful expedition and several short transportations around the Baltic. Something had to be done…

The first thing to do was work hard. This proved productive; on 7th May the following year he was promoted to ‘high boat man’ (högbåtsman), though as there was actually no vacant position he had to continue working as an artillery expert until further notice, so for the time being it was merely a title. He was once more ordered to go to Riga on the vessel Solen for mast timber, followed by another trip to Stralsund for oak timber.

This latter voyage ended in a perilous situation when strong contrary winds forced them to seek refuge in the harbour of Karlshamn in Blekinge on 10th December. On the way in, they hit one of the plentiful rocks in the area. This the ship survived, but when they had finally fought their way into harbour and anchored at the local fort, the sea froze over, and the ship had to be abandoned as the ice closed in around it. Of course, they could not just leave the ship in the wrong harbour without permission from their superiors, so Gabriel had to hurry to Karlskrona on horseback in order to obtain authorisation to leave the ship and let the crew walk the 60 km back to Karlskrona on foot.

What a Christmas! It must have been a really cold ride. He certainly fell ill immediately after New Year’s eve and was permitted to go home for 3½ months to recuperate.

He was not sorry for this opportunity of seeing his beloved Anna Brita again. Now that she had had time to consider his proposal properly before committing to it, he asked her whether she was still prepared to stick to their secret plan of marriage. This he found that she was.

19th [January 1726] I travelled and arrived home 23rd and during the home visit my marriage pact was ratified to last unconditionally.

Translated from Swedish

He was now a happy man, if only he could rise through the ranks.

Gabriel was at Liljeholmen when the final trial regarding his sister and Georg Ramberg was concluded in March 1727. In April he returned to Karlskrona, where he was permitted to travel on his own for a couple of years in order to learn his ropes (euertera sig uti navigation). It was in effect a sort of 17th century ‘interrail’, with all the uncertainty and unpredictability that such journeys involve. Highly interesting and very instructive for a young man, but also somewhat dangerous, and impossible to plan. It would be almost eight years before he was back in regular service in Karlskrona.

Now take a look at him with your mind’s eye, and it is a brave man that you see before you. He is very much looking forward to roaming the seas for a few years, but he has just made a pledge of eternal love to a very young girl and has a new responsibility to shoulder. His first priority must be to return alive and well, and his second to ensure that they will have something to live on. He must educate himself by improving his naval skills, but he must also ensure that the Liljeholmen estate will truly be his in time. What if his father were to die while he is away (as in fact he will), and someone pretended to have a greater claim on the estate than him? Before leaving the parish, he makes sure to contact the local authorities and ask them to register his request that nobody cheat him of his proper inheritance while he is away. They agree to write it down, but refuse to make a formal promise that his demand will be acted upon. He has done his best, however, and now has only to depart and enjoy.

During the next couple of years he makes several voyages to Amsterdam and Cádiz, sometimes as a humble sailor, occasionally as a vice constable. Both towns must soon have started to feel like home.

The first of these travels appears rather improvised. On 14th June he left Karlskrona on a ship commanded by skipper David Sellnaw from the Pomeranian town Wolgast, who was going to Amsterdam. They had to go past Copenhagen and Elsinore, where they were duly taxed 2nd July, as were all ships passing through the Danish sound.

They arrived in Amsterdam on 6th July. The first two nights were spent on board, but then he found lodgings with a skipper’s widow Christina Brown, so he carried his things off the ship and signed out with the captain. Four days later he spotted a frigate in the harbour and contacted the captain Charles Segenberg in the hope of being allowed to go with him to Cádiz on the stately King David, and after two days in Amsterdam they were off.

Reaching the open sea from Amsterdam in those days was a laborious business. They left the harbour on 14th July, and nine days later were convoyed north towards the open sea, only to anchor at the island of Texel for nearly two months until the winds were favourable on 23rd September.

Out on the North Sea things moved a bit faster. They reached the English Channel in just two days, but on entering it were hit by such strong winds that they were forced to return with great difficulty. Finding themselves back at Texel must have been highly frustrating. A whole month would pass before they could leave again, this time finally managing to get through the treacherous channel by the end of October and arriving in Cádiz on 16th November.

After several return voyages between Amsterdam and Cádiz, he found himself in the latter town in August 1729. There, the ship he had arrived on was sold to the Spaniards for 54000 riksdaler specie. This cannot have been the King David, for that was still under the command of Charles Segenberg a year later, when it was captured by the Moors in an international crisis, which might have ended very badly. Gabriel was very lucky not to be present on that trip.

The King David had been involved in similar troubles before, notably in 1669 when it was attacked by Alger pirates and only escaped when other British ships defended it in a veritable battle at Cádiz. This time, however, they were not so lucky. The following letter was written by captain Segenberg on board the King David on 29th November 1730.

Le 3. du courant à la pointe du jour, étant à 30. lieuës du Cap de St. Vincent, nous rencontrâmes deux Corsaires d’Alger, montés chacun de 50. pieces de Canon, qui nous obligerent, de même que le Capitaine Schelvis, avec qui nous étions partis de Cadix, de mettre nos Chaloupes en mer, & d’aller leur montrer nos passeports. Ils dirent qu’ils étoient obligés de nous conduire à Alger, sûr ce qu’ils trouvoient nos passeports trop vieux : ils firent ensuite passer sur leurs bords l’Equipage de nôtre Vaisseau, & celui du Capitaine Schelvis, à l’exception de cinq hommes, & en échange ils mirent sur nôtre Bâtiment 40. Turcs, qui s’emparerent d’abord de tout, ouvrirent même & mirent en pieces les ballots, pacquets &c. pour voir les marchandises qu’ils contenoient. Ces Corsaires nous emmenerent tous deux ensuite à Alger, où nous arrivâmes le 20. du courant; & nous trouvâmes qu’on y avoit aussi conduit les Bâtimens des Capitaines Jean Colster & Atis-Vroom. Les Turcs firent de grandes démonstrations de joye, sur la prise considerable de ces 4. Vaisseaux, qui avoient été enlevés sans qu’il leur en eut couté un coup de poudre. Mais les Consuls de France, d’Angleterre & de Suede se joignirent d’abord à celui d’Hollande, & representerent trés-vivement au Bey, qu’il devoit relâcher ces 4. Vaisseaux avec leurs Equipages & cargaison, ou qu’autrement il devoit s’attendre que leurs Principaux lui en témoigneroient leurs ressentimes &c. Le Bey ayant fait la dessus assembler le Divan, il y fut résolu de relâcher les Bâtimens & leurs Equipages, mais de confisquer l’argent comptant, & les autres effets qu’on y avoit trouvé à bord : sur quoi lesdits Consuls s’étant de nouveau rendus chez le Bey, lui firent de nouvelles remontrances, ausquelles ils joignirent quelques menaces, qui eurent cet effet, qu’il nous remit d’abord tous en liberté, & nous rendit l’argent comptant sans le compter, quoique la populace se fût déja soulevée contre lui, avec menace de le massacrer, sur ce qu’il rendoit ainsi ces quatre prices avec tout ce qui leur appartenoit. Cependant nous fimes toute la diligence possible, & nous mimes en mer, non sans peril, de compagnie avec le Capitaine Schelvis ; mais les Capitaines Jean Coster & Atis-Vroom nepûrent nous suivre ce jour-là, parce qu’ils n’étoient pas encore prêts. Nous faisons actuellement voile pour Gibraltar, afin d’être radoubés, & de nouveau pourvûs de toutes sortes de munitions, les Barbares nous ayant tout enlevé.

Put briefly, it was a passport inspection gone wrong. The passports were claimed to be too old, and several ships were brought to Alger, where the locals took possession of the vessels and all their cargo and money. Under violent protests from the consuls of the mercantile superpowers England, France and Sweden they were finally allowed to leave Alger, but as the Algerians had disarmed them they did not feel safe until they had been to Gibraltar and obtained new munitions. Clearly, these trips were dangerous in many ways.

When Gabriel’s ship was sold in Cádiz, he contacted an English frigate, where he was taken aboard by Captain Brown as a constable. They left for the Italian town of Genoa on an autumn day, passed Gibraltar without incidents on 20th September and entered the Mediterranean for the first time in his life. In Genoa, he secured a place on another English frigate by the name of Johanna; Captain Martin was on his way to Alicante in Spain, but they seem to have gone on to Cádiz.

It was while lodging there that he got the letter about his father’s death at Liljeholmen. Gabriel was only 26 years old, but he had seen the world, and his father’s death was no reason to go home. After all, his beloved Anna Brita would not turn 18 for several years, so he was in no hurry to get back. Instead, the next couple of years saw him leaving on a ship bound for the very ends of the earth. A huge and perilous adventure was awaiting him.

The long voyage

On 14th January 1730 Gabriel left Cádiz on an English frigate bound for London, whence a month later he continued to Rotterdam on a small piquet boat under the command of skipper Krawa.

He then started to get some more interesting assignments. He was at first really excited when he was entrusted as a constable on a Dutch ship from Amsterdam with 28 guns, but unfortunately the ship turned out to be so leaky that they had to return her to a shipyard. He was therefore forced to look for another job, and that was when he found the Klarabeek. He was going on a long and perilous adventure, which was to take him all the way to South Africa, Jakarta, Sri Lanka, and Mecca.

The ship in which he invested his fate, the Klarabeek (occasionally referred to as Klarenbeek, and thought to be named for a place outside the ship’s home port Middelburg in the Netherlands called both Klarebeek and Klarenbeek), was commanded by Captain Christiaan van Damme and was bound for the East Indies. They set out from Rotterdam on 2nd May 1730, passing by Fort Rammekens at Middelburg further down the coast 11 days later, possibly to pick up the last members of the crew, which consisted of 121 seafarers, 66 soldiers and 6 craftsmen.

Navigation in those days was cumbersome and dangerous and wholly dependent on the prevailing winds and currents. They first spent a week in Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, probably to collect enough provisions. The voyage around the Cape of Good Hope could only be accomplished by following the winds across the Atlantic almost to South America, before turning sharply and following another current towards South Africa. On August 4th they crossed the Equator for the first time in Gabriel’s life. Even after many years at sea, he had never experienced anything remotely like this testing voyage across the open Atlantic. When they reached the Cape on August 13th, the adventure was already taking its cruel toll of human life.

6th [November 1730] we weighed anchor and set sail to continue our voyage which was still 1500 miles to Batavia [i.e. Jakarta]. Here I would like to add that in this aforementioned Cape we fetched fresh water and fresh food and at the same time also received healthy men in place of 12 dead out of a little over fifty, so that the numbers of our crew were again as before, when we set out from Amsterdam 180 souls, but we left our sick in the local hospital.

Translated from Swedish

It is clear from other sources that what he means is that 12 people were dead out of 52 who had fallen ill. In actual fact, only 9 were dead while the last three left the ship at the Cape in favour of the Windhond, which was also anchored at the Cape, one of them replacing the first mate there. The two ships travelled in convoy for safety; there were still many pirates around, and even in a storm having two ships could save lives if one of them were to perish. The replacement crew from Cape Town consisted of 18 seafarers, 7 soldiers and 2 craftsmen.

It would get much worse than this. True to his style, he does not seem keen to admit of any sickness himself. In fact, he seems to imply that he is one of the only healthy and truly helpful men on the ship, right until the very end when the truth comes out.

If what Gabriel tells us is true, then the amount of sick people must have been truly horrendous. The Dutch secretary at the fort in Batavia tells us that on this part of the journey a further 13 seafarers, 12 soldiers and 1 craftsman died, so that on arrival in Batavia they were left with 99 seafarers, 34 soldiers and 6 craftsmen. We can now calculate the brutal statistics of seafaring in the 18th century:

- Crew at departure from Fort Rammekens 13/5 1730: 121 seafarers, 66 soldiers, 6 craftsmen = 193 men

- Dead before arrival at the Cape 13/8 1730: 7 seafarers, 2 soldiers = 9 men

- Moved to de Windond at the Cape: 2 seafarers, 1 craftsman = 3 men

- Sick people left at the Cape: 18 seafarers, 25 soldiers = 43 men

- Replacement from the Cape: 18 seafarers, 7 soldiers, 2 craftsmen = 27 men

- Total crew after the Cape 6/11 1730: 112 seafarers, 46 soldiers, 7 craftsmen = 165 men

- Dead after the Cape (at least): 13 seafarers, 12 soldiers, 1 craftsman = at least 26 men (Gabriel says 124 men)

- Replacement at Bantam: perhaps as many as 55 men

- Arrival in Batavia 5/3 1731: 99 seafarers, 34 soldiers, 6 craftsmen = 139 men

The numbers in the sources do not reveal any replenishment of the crew at Bantam, and Gabriel tells us that ten times as many people as registered in the sources died but were replaced before the arrival in Batavia. In that case, perhaps as many as 55 men were added in Bantam, assuming that everybody survived the last leg of the voyage to Batavia, which is by no means certain.

The calculation is based on a comparison of Gabriel’s numbers with those in the official archives of the Dutch East India Company back in Holland on the one hand and the numbers noted in the Indonesian Sejarah Nusantara archive of matters relating to the Dutch rule on the other. The Indonesian archive is a treasure trove of information from the fort in Batavia, and well worth the effort of seeking out and deciphering the relevant documents written in 18th century Dutch and Malay. On 3rd March of that year, for instance (according to the Dutch calendar as opposed to the Swedish), a Chinese messenger had knocked at the door in the Dutch secretariat in Batavia to deliver a letter from Bantam reporting that the Klarabeek had arrived and that assistance had been given to the crew.

3rd [March 1731] reception of a Bantam letter to the effect that Klarabeek had arrived at the Sunda Strait.

Translated from Dutch

Two days later, the fort secretary registered their arrival in Batavia.

arrival to the Batavia roadstead by the ships Klarabeek and de Windhond from the Netherlands

Translated from Dutch

They brought with them quantities of unconsumed meat, bacon, French and Rhenish wine, vinegar and various kinds of European fabric.

Gabriel assists the sultan of Palembang

When he had recovered from his illness, Gabriel was picked up by another ship, and this leads directly to what is perhaps the most surprising of all Gabriel’s adventures in the East Indies.

Indonesia at the time comprised a range of lesser kingdoms controlled by the Dutch, and by assisting certain kings the Dutch consolidated their own power in the area. In this instance, the secretary at Batavia Fort had received a letter on 26th January 1731 from sultan Mahmud Badaruddin I of Palembang who needed assistance to withstand a Bugis revolt in favour of prince Dipati Anum (who may have been his son, but this is unclear), in the tin-producing island of Bangka.

The Buginese are a people from southwestern Sulawesi who had settled in Bangka and southern Malaysia, where they had become very powerful. They had helped the Malaysian Johors defeat the old Jambi sultanate in the 17th century and were now closely allied with the Johor sultan.

As tin from the twin islands of Bangka and Belitung had been gradually replacing pepper as the Palembang sultanate’s most lucrative trade item during the reign of its current sultan, retaining control over these islands was crucial. The tin miners in Bangka were mainly Buginese, so their powerful compatriots naturally wanted their share in the profits.

We know that the Dutch expedition to Bangka was successful, and that the sultan continued reigning until 1754, but Gabriel tells us nothing of the actual events. Luckily, the Palembang and Dutch governments communicated by letter. The secretary in Batavia not only kept a journal of what letters he received, but also copied many of the letters in translation from Malay.

In his first letter, the sultan had reported that his foe had been joined by the rogue Arong Mapala and his troops who had gone to Bangka and were now busying themselves with harrassing the locals.

Furthermore, Paduka Seri Sultan Ratu [i.e. Mahmud Badaruddin] makes known to this his brotherly friend the Governor General and Councillor of India that prince Dipati Anom has joined with Arong Mapala and his troops which now find themselves in the island of Bangka and are busy oppressing and harrassing the islanders.

Translated from Dutch

He added that, as he had no one else to ask for help, he was hoping that the Dutch would assist him in his hour of trouble.

On 1st February, an emissary was sent back to the Palembang sultan with reply that assistance would indeed be given. Accordingly, a Dutch expedition was ordered to leave for Bangka, and Gabriel was told to participate in this quest.

4th March [1731] I was ordered onto the admiral’s ship Hasburg [Heesburg], which was commanded by Captain Martin Martål [Minut?], which along with three other ships was ordered to assist the local heathen king, as his subjects had in mind to murder him and take his son as their king instead.

Translated from Swedish

He probably looked forward to some action, given that he would later deplore the fact that he had never been involved in any naval battle.

Note: The ship Heesburg seems to have been under the command of skipper Jan de Marre at this time, according to Dutch sources, but in one of the letters from the sultan a captain by the name of Jan Minut is mentioned, and he may possibly be the same person. It seems highly likely that the very strange name Martål is simply the diary publisher’s misreading of Minut (with a half-circle above the u as was usual at the time). Whether Gabriel mixed up the two captains’ names or Martin Minut was a relative of Jan’s, we don’t know.

On 26th March, a letter arrived from Palembang to inform the Dutch that the Buginese rogue had been surrounded in Bangka, but had been rescued by his ally, the usurper Sultan Dipati Anum.

(…) news that the Buginese robber Arom – Mapala with his adherents had been surrounded by the Palembang people at sea, but had been rescued by the usurper Sultan Anum who was staying on Bangka Cobo (…)

Translated from Dutch

The rebelling sultan had left Linggi south of Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia and had established himself on Bangka ”with his entire train of wives and children” (met zijn gantsehen Sleep van wijven en kinderen). Linggi was the seat of power in the Johor empire, so presumably he had been talking things over with his allies.

The next letter did not arrive until October, indicating that the Palembang sultan had been busy consolidating his power. This he did very successfully, and he is generally considered a wise and considerate ruler. After the rebellion had been quenched, Sultan Mahmud Badaruddin invited thousands of Chinese miners to Bangka so the Buginese would never be able to take control on their own again. He had married a Chinese woman himself, and a total of around 25,000-30,000 Chinese came to the area during his reign.

The sultan was very happy with the help he had received, and he told the Dutch so in his jubilant letter of thanks. He explained how things had developed. Briefly, the Dutch captain Jan Minut and his men had rushed to the island with the royal entourage and their vessels equipped for war. They met the opponent on the road to Bangka Kota whence he had fled to an unknown place. Captain Jan Minut thought he might have fled to the fort at Pangka [Pangkal?] and took his men there, but found the nest empty. They could not search the harbours and rivers properly before it was too late, because strong contrary winds and bad weather kept them from setting out to sea. The sultan added that the miscreant’s escape was fully due to the negligence of the Palembang folk and in no way to the actions of the Dutch. According to some prisoners who had been caught, Dipati Anom had fled to the neighbouring island of Belitung or Lampung in southernmost Sumatra, with four local vessels. No exact destination could be ascertained, however.

A company of Palembangers then left for Tanjung Ular with captain Roos, where they found the rogue Arong Mapala. They immediately attacked the place and conquered it, but he burnt down the houses and succeeded in escaping and disappearing completely. They then continued to the island of Belitung, where the locals made no attempt at protecting the rebel but handed him over to captain Roos directly.

Here is the original letter in case someone is interested.

Hebbende gemelde Heer Oostwald voorts naar verloop van eenige dagen omme te voldoen aan de goede intentie van de Padoeka Sirij Zulthan Ratoe werkstellig gemaakt alle ’t geene streek ende was tot heijl en wel wesen van den Padoeka Sirij Zulthan Ratoe en tot ruine van de genen die hebben derven onderstaan ’t coningrijk Palembang en de dies resorten te ontrusten ende in leijelijkheeden(?) toetebrengen en ter den eijnde sig perzonelijk begeven na’t eijland Bangka met de capitain Jan Minut en ’s EComp:t magt gevolgt van alle de Pangerangs en verdere onderdanen den Padoeka Sirij Zulthan Ratoe met hunne toegeruste vaartuijgen aan dat eijland gekomen sijnde van sijn Edele deroete na Banka Kota van vaar ten eersten den pangerang Dipattij Anom te kobak ging attaqaeren en op de vlugt slaan sonder dat men tot nog toe heeft konnen te weten komen vervaard hij met de sijne geretireerd is ende den capitain Jan Minut die met zijn gevolg na de vijandelijke pagger te Pangka was gedetocheert heeft aldaar de pagger ledig en sonder menschen gevonden alsoo al het volk neets voor zijne aancomste gevlugt waren.

De oorsaak nu waarom men genoemen pangerang Dipattij Anom niet heeft konnen in handen krijgen is om dat de Palembangers die uijtgezonden waren om alle de havens en rivieren te bek:t ten door tegenwind en swaarweer sijn belet geworden tijdig de plaatsen daarse post maester vatten met hunne vaartuijgen te bezeijlen zij hebben vervolgens alle de havens en rivieren onderzogt dog geen vaartuijgen ergens ontwaart waar mede hij met sijnen aanhang van Bangka souwde konnen vlugten met(?) malt dier halven voor seekerstellen dat hij naderhand van die geene die in zee swerven van het eijland is afgehald en weg gevoert soo dat het ontsnappen van genoemde pangerang Dipatti Anom eijgentlijk gecouteert is door de negligentie van de palembangers maar geensints door die van de heer Oostwalt voornoemt en volg: de berigten van de gevangenen die gekregen sijn soude pangerang Dipattij Anom en sijnen aanhang met vier Bangkase vaartuijgen gevlugt wesen na Blitong of te na Lampong sonder dat men voor als nog met waarheijt seggen kan waar hij sig onthoudt sullen de dier halven den padoeka Sirij Zulthan Ratoe met marqueren daar na te laten vernemen ende ten spoedigsten uw Hoog Edelhedens mede deelen.

Ook werd den Heer Gouverneur Generaal ende raden van India bij desen mag ter kennisse gebragt dat met de Eenste aancomst alhier van den heer Oostwalt men gooedgevanden heeft den capitain Roos met nog eenige Palembangs groeten te detacheeren na Tandjong Oelar en Blito die met zijne aankomst op Tandjong Oelar aanstonds die plaats geattaquiert en overnommen heeft dog Arom Mapala heefd sig met de vlugt geeschapeert en is niet agterhaalt geworden de huijsen aldaar afgebrand zijnde hebben de onse haar verders begeven na Blito welker volkenen geen vijandelijkheden hebben betoont maar aanstends haar overgegeven in handen van capitain Roos voornoemt.

Wijders wat aanbelangt uw Hoog Edelh:s vriendelijken onderwijsingen en vermaningen sneels(?) bij de hoog geagte brief aan den Heer Gouverneur Generaal ende de raden van India daar op betuijgt den padoeka Sirij Zulthan Ratoe niet te sollen manqueeren na smagen(?) te bevlijtigen ende sorge te dragen an die in allen deelen op te volgen ende naar te komen ende dus volkomen voldoeninge te geven aan de vermedelijke vermaningen en onderwijsingen van den Heer Gouverneur Generaal ende raden van India sullende den padoeka Sirij Zulthan mooist uijt zijne geheugen laten gaan den vrundelijken bijstand en bescherminge van desselfs ware wunden en getrouwe bondgenoot den Heer Gouverneur Generaal ende de raden van India maar steeds daar op sijne hoop en vertrouwen stellen betuijgende midellerwijle daar voor sijne veelvoudige dankbaarheijt bij desen omtrent desselfs waren runden(?) den Heer Gouverneur Generaal ende raden van India.

Eijndelijk wer uw Hoog Edelh:s nog ter kennisse gebraagt dat ’t eijland Bangka thaus door de goetheijt en veel vermogende hulpe van den Heer Gouverneur Generaal ende raden van India gesuijvert is van al ’t geene eenig an heijl zoude konnen veroorsaken want alle de volkeren hebben haar weder aan der padoeka Sirij Zulthan Kamer onderwepen in dier volgen als van ouds gewert is.

Ges:z in de stad Palembang op het gesegenste landschap van ’t eijland groot groot andaloes int haar na de vlugt des propheets 1444 op donderdag den 10 van de maand rabint awal int jaar Ba.

Trading in India and Mecca

After this brief interlude of official excitement, things went from thrilling to really challenging, even for the hardy Gabriel. In fact, this is one of the only times we ever hear him complaining, in spite of all the hardships he had already been through. After a month of cruising the Bantam coast with the Heesburg, presumably to ensure safety in the area, he finds himself back in Batavia.

8th [June 1731] we set out from there and came 3 miles thence; during night and day we had had to haul the ship [onto land for repairs], which was fairly leaky, whereby we had a rather difficult job through night and day, and no more than 1½ stuiver [Dutch currency] a day to live by; hence the men were mostly sick and dead of dysentery, an illness which also overpowered me; additionally I had severe wounds in my legs, so that I was brought from there to Batavia Hospital on 12th July, where I lay till 1st September, when I was ordered on the ship Het Land van Beloofte with Captain Giulkus Oudeman [Gillis Oudemans] going through the Red Sea 1500 miles to a place called Mocka [Mecca] in Arabia.

Translated from Swedish

You can hardly accuse him of making a fuss.

The idea of this new trip was to ship a load of pepper from India to Mecca, where they would then collect coffee beans for the European market. They left Batavia on October 1st and anchored at Punnaikayal on the Malabar coast of southern India on 9th December. There they stayed for Christmas, setting out again on the 28th.

Note: He calls the place Pontugale, which is rather similar to its Portuguese denomination Punicale. There seems little doubt, therefore, that Punnaikayal is the place intended.

In January they arrived in Cochi in Dutch Kerala, where they got the pepper. On 29th February, they made a brief stop in Dutch Ceylon, where they left a noble Dutchman which they had brought there, probably from Batavia. He was to be the new governor of Ceylon, at least for a short time (25/8 – 2/12 1732), and his name, according to other sources, was Gualterus Woutersz. He was originally from Middelburg in the Netherlands, but had spent many years both in Ceylon and in Batavia.

They finally reached their Arabic destination on 6th April, but were in for a disappointment. While the pepper was well received, the local Dutch commissary had failed to purchase the coffee beans that they were supposed to take with them, and consequently they were forced to leave empty-handed. We have no idea how Gabriel spent the four months they were at anchor in Mecca. It must have been an exciting time for him, but his diary leaves one with the impression that his life was lived at sea, while the brief stops on land were insignificant gaps. They left Arabia on 20th August 1732 and reached Batavia on 19th January. On this journey, he worked as a constable.

A month later they continued to the fortified island of Onrust (Pulau Kapal in Indonesian) just outside Batavia. This was an important part of the Dutch military establishment in the East Indies and included a wharf and other naval facilities. Captain Cook was one of those who would stop by on the island on his way to explore Australia in 1770.

While on the island, Gabriel became seriously ill again, this time from a fever, and he was sent by boat to Batavia hospital for the third time. He only remained at the hospital for 5 days, however, and on 15th March he secured work on the Berbices (read by the publisher as Barbilie), which was to leave for Holland on 6th April with captain Cliefs, no doubt a certain Captain Joris van Kleef. Other sources make it clear that the old ship Berbices, built 1709, must have turned out to be too battered to manage the long return voyage. Having done her last duty when arriving in Batavia in 1727, she was officially decommissioned there in 1734 (31st October 1733: Baanman, Arend, Vaderland Getrouw en de Berbices binnenkort worden afgelegd), and we know that Captain Joris van Kleef actually ended up making the voyage on the Alblasserdam. His dates correspond to those given in the diary, so it would seem that Gabriel was actually brought home on that vessel too, even though he does not mention the change of ships.

They stopped at the Cape of Good Hope on 17th June, continued on 2nd July, and arrived at Texel in Holland on 8th October.

Both Klarabeek and Het Land van Beloofte would return to Holland in October that year as part of a convoy consisting of 11 vessels. These ships returned with a rich cargo of spices and exotic wares, as advertised in the Europische Mercurius (see the excerpt). They even brought some tin from the Bangka mines.

Captain Gillis Oudemans was later committed for corruption along with three other officers aboard the Haapburg, which had returned with that same convoy. They were fined and sent back from Batavia to the Netherlands in disgrace.

The Alblasserdam only ever made one successful voyage after Gabriel left it, as it sank at Canton in 1735, and the Klarabeek foundered in the Indian Ocean in 1740. Once again, Gabriel was lucky not to be on the wrong ship at the wrong time.

Home again

Setting foot on the European continent once more was an emotional experience for Gabriel. This is the first time we sense his emotions on this long journey; he is deeply thankful to be back alive and well.

8th October [1733] to Tessel [Texel]. On the 12th we came to Amsterdam with much joy that God graciously had wonderfully brought me so far on the return voyage against all expectation.

Translated from Swedish

On 1st November he left for Stockholm with Swedish Captain Jacob Georg Hupenfelt on the frigate Charlotta Eleonora bringing salt, fish, lemons, fabrics and tobacco for the Swedish market. On 1st December they anchored by Copenhagen, and another fortnight saw them in Stockholm.

His family and his beloved Anna Brita received a very special Christmas present that year, as he returned to Liljeholmen at 7 pm on Christmas Eve 1733.

8th [December 1733] we arrived in Kalmar and the 14th in Stockholm, and the 24th Christmas Eve at 7 pm I arrived at Liljeholmen through the gracious God’s wonderful assistance and help, and for that be his thanks and praise eternally Amen.

Translated from Swedish

He had not seen his home country for more than seven long years, and what a time he had had!

One person in particular had a claim on Gabriel’s interests, and the very next day he hastened to meet her at Somvik in the neighbouring parish of Malexander. For some reason, it took another day before they met by Malexander church. In just six days she would be 18 years old, on 1st January 1734. What perfect timing!

It seems he somehow and at some unspecified point succeeded in getting her family’s permission to marry her, but that was not enough; as she was of noble stock he also needed a royal permission. This could take some time to achieve, so they had to be patient.

Note: The Wetterström family does not seem to be registered as nobility, so the reason for the need for a royal permission is unclear.

He therefore returned to Karlskrona to take up his work as master of artillery again. The letter from the royal office did not arrive until 3rd July 1735, so it proved a long wait. Bans were proclaimed from 12th October, and the happy couple were finally married on 12th November. For once his pen is downright garrulous, but though I used to ascribe this to his strong love, it may also be interpreted as the result of his sense of duty towards his betrothed as well as to God, to whom he had equally made a promise and by whom he had been kept alive through seven perilous years.

12th November [1735] I was married to the aforementioned virtuous maiden with whom I then had already promised by God as I wanted him to help me wherever I ended up in the world sooner or later, that I would never abandon her, providing God did not meddle by way of death or any unlawful hindrances [possibly in the sense of infidelity?], as I also wanted to honour my good oath without [bad] conscience.

Translated from Swedish

One would hope, at least, that they were in love, and from the various sources available to us it certainly appears that they were a happy couple. One thing is certain: Unlike his parents they had no less than eleven children over the years, six sons and five daughters.

Less than a month after the wedding, joy was mixed with grief as Anna Brita’s father died. In February, Gabriel was forced to leave her to her grief at Liljeholmen in order to do his duty in Karlskrona where he was commanded on the cargo ship Stjernan, but when her mother also died in April, he made arrangements with the navy to the effect that he could take the following year off in order to care for his estate, which was probably in serious need of attention at this point. His stepmother was buried in the old family tomb of the Gyllenståhls.

1738. This year I was mostly on leave in order to care for my wife’s inheritance and ancestry, my own affairs, which consisted in conserving my own future inheritance, and to ensure that the estate Liljeholmen with its property be in such a state of construction and repairs that it could be productive of some use.

Translated from Swedish

If his expressions appear somewhat commercial, given that one would expect him to look forward to spending more time with his wife, one should remember the economic plight the formerly wealthy family was in at this point. As we saw in chapter 5, Gabriel had to work very hard to get the family back on its feet by reinventing the way agriculture was done in the area. In time, he would succeed in this venture, but he certainly needed all the initial capital he could get to set him off.

It was therefore a good thing when he was shortly afterwards promoted to ordinary master of artillery. This probably meant that he was now actually paid at a level corresponding to the work he had been doing for some time. He spent the year 1739 on land, probably at Karlskrona. In 1740 he was promoted to ordinary constable, the year after to extra lieutenant on the Fredrica Amalia, and 1742 to ordinary lieutenant on the ship Skåne. His last voyage with the navy he completed in 1751, when he transported the Swedish land army from Pomerania to Åhus in Scania on the ship Portryttaren.

By then, thirty years had passed since he was first enrolled in the navy. It had been an eventful period of his life; now he had to settle down and learn to be a full-time landlord as his father before him, but hopefully a more successful and likable one.

A ship of his own

When Gabriel had retired from the navy and returned to Liljeholmen for good, it is only natural that he should sometimes be missing life on the sea, feeling the wind in his hair and being in command of a vessel of his own. Being back on land was not so exciting. According to his merit list, he was rather disappointed at not having been involved in a single naval battle, but then he had seen so many other things that very few Swedes could dream of!

To ease his longing, he set out to build his own ship with keel and sails just like a real frigate, but with the somewhat more peaceful function of transporting the family to the church in Torpa.

The traditional way of crossing the lake Sommen was in a boat of the type Sommaskep, which evolved on this lake. They were large rowing boats with three to four pairs of oars, and they were therefore particularly suited for long journeys on the large lake. Sommaskep were built as late as the 1960s, and the tradition has recently been revived.

Though large for rowing boats, the sommaskep were of course far from sufficient for Gabriel’s taste. Unfortunately, while he may have been a hardy and fearless mariner, he was no shipbuilder like his grandfather; the vessel became a complete fiasco.

Many of the locals helped him (they probably could not refuse), and they did eventually finish a large ship to his design. When it was ready, the assembled people boarded it, weighed anchor and started their journey across the lake. To Gabriel’s dismay, they only got 2.5 km before the ship hit the bottom and ran aground at Munkhallen. They were forced to get several sommaskep from the nearest estate at Brandsnäs on the island of Torpön in order to pull it free. After a lot of hard work they were finally able to continue their journey towards the church, where the priest was probably waiting for them to approach before chiming the bell, as this was an old practice instituted by Gabriel’s predecessors; service must not start before they arrived.

Unfortunately, a couple of kilometers from their destination the ship once more hit ground at the rock Mellsberget. This time it was so badly damaged that they had to tow it back to Liljeholmen with great effort. He never got it back in sailing condition; it lay rotting at Liljeholmen for many years, the laughing stock of his enemies who ridiculed his ambitious attempt, or as the local Daniel Burén would later express it in his diary where he collected people’s accounts of past events of local historical interest:

(…) its hull lay for many years, the laughing stock of Ahlfort’s enemies and such people in general who do not have the brains, audacity or power to hazard anything in new enterprises or realize them, but on the other hand they are particularly clever at criticizing other people’s failed attempts and reproaching them for them.

Translated from Swedish

This sums up Gabriel’s personality nicely. He may occasionally have been a local object of ridicule, but in things that really mattered he succeeded brilliantly and was respected and remembered at least for a time at the national level.

Selected sources for chapter 7

This text is a synthesis of several years of work and is derived from countless sources. Among them are the following.

- ArkivDigital / Riksarkivet

- Church registers

- Naval registers

- Från Sommabygd till Vätterstrand VI

- The Elsinore taxation records

- Sejarah Nusantara

- The Dutch East India Company’s shipping between the Netherlands and Asia 1595-1795

- De VOC site

- Michael Wanner: The Madagascar pirates in the strategic plans of Swedish and Russian diplomacy 1680-1730

- Fredrik Sjöberg (2012): Varför håller man på?

- Evgenii V. Anisimov, J.T. Alexander (1993): The Reforms of Peter the Great: Progress Through Violence in Russia

- La clef du cabinet des princes de l’Europe (1730)

- Europische Mercurius (1734)

- Bernardus Mourik (1752): Twee rampspoedige zee-reyzen, den eenen gedaan door den Ed

- M. C. Ricklefs (2008): A History of Modern Indonesia since c. 1200

- Digitaliserade svenska dagstidningar (Digitized Swedish newspapers)

- C. D. Burén’s notes

02-12-2023

Lämna ett svar